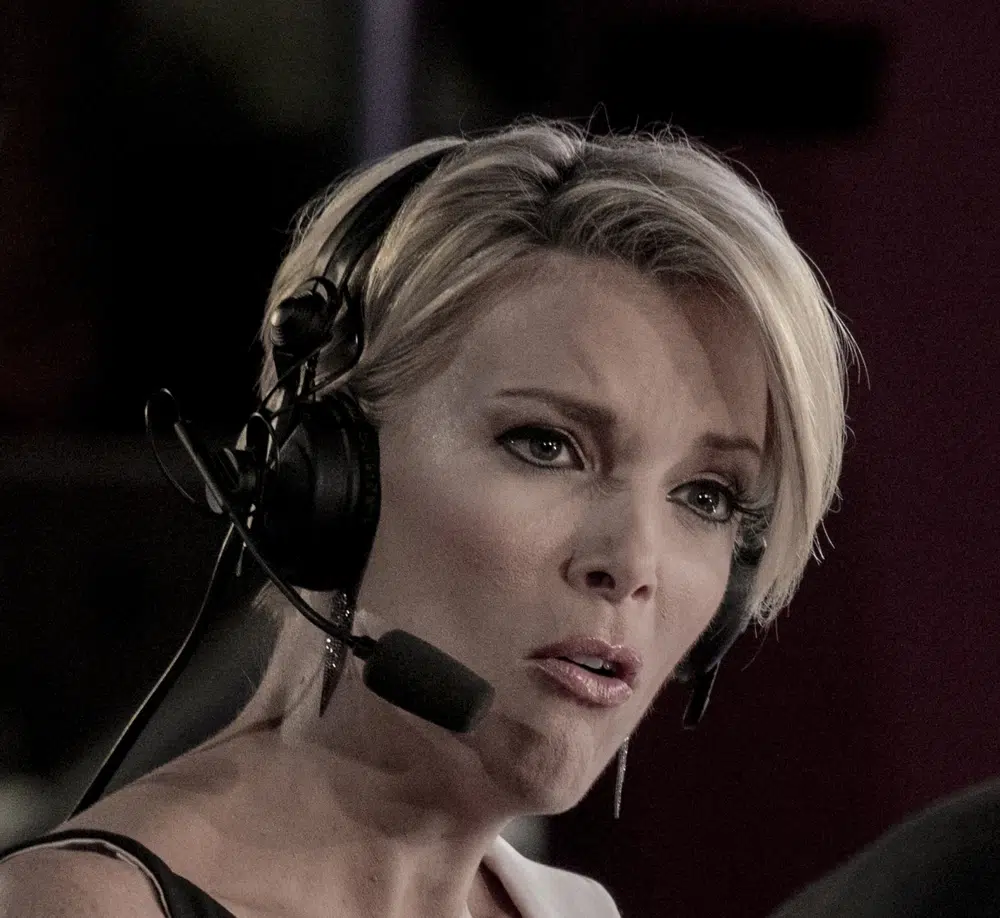

A prominent survivor of Southern Baptist Convention clergy abuse has issued a forceful response to comments made by podcaster Megyn Kelly, who recently suggested that Jeffrey Epstein preferred what she called “the barely legal type.”

Christa Brown, a longtime advocate for survivors and a former appellate attorney, says Kelly’s remarks minimize the rape of children and reinforce the same cultural attitudes that enabled her own abuse by a Southern Baptist youth minister when she was a teenager. Brown argues that such rhetoric causes widespread harm to survivors and contributes to a dangerous misunderstanding of how predators exploit minors.

According to Brown’s article, originally published on her Substack and republished on The Roys Report, her perspective was shaped by her own experience of being groomed and abused by a Southern Baptist youth minister when she was 15 and 16. She recalls that she still wore braces and later a retainer, details that underscore how unequivocally she was a child.

Brown explains that the pastor used religious authority to manipulate her, ending each assault by saying “God loves you, Christa,” which she describes as part of a larger pattern of spiritual distortion and control. She argues that comments like Kelly’s erase the reality of how predators exploit the vulnerability of minors who are far from anything resembling adulthood.

Brown says other pastors knew about the abuse and did nothing. She claims that much like Kelly’s remarks, these leaders functionally minimized what happened to her by reassuring themselves that at least she was not eight. Brown argues that this mentality is part of a broader pattern in the Southern Baptist Convention, where she has spent years trying to raise awareness about systemic abuse and the failures of leadership to intervene.

In the article, Brown includes a photograph of herself as a teenager and says she still wore hairbows, emphasizing that she was unmistakably a child. Brown argues that there is no such thing as “barely legal” when an adult in a position of power exploits a minor. She says all child rape is an abomination, regardless of the victim’s age. Brown urges Kelly and others to stop minimizing and parsing abuse in ways that protect predators.

Throughout her advocacy, Brown says she has repeatedly confronted a culture within the Southern Baptist Convention that encouraged deference to male authority and obedience to pastors. Brown suggests that predators exploited this theology to groom and silence victims. She points to years of documentation showing that some SBC leaders dismissed survivors, concealed allegations, or moved accused pastors to new churches. Brown says that when she first reported her youth minister decades later, church leaders questioned her memory and suggested her suffering “may” have come from something unrelated to the perpetrator.

Brown argues that this gaslighting pushed her into deeper advocacy. She collaborated with another attorney to request non-litigation remedies, including a memorial garden for victims and counseling support. Brown says she later discovered her perpetrator was still serving in children’s ministry. She also found evidence that the Baptist General Convention of Texas (BGCT) kept a confidential file of clergy offenders but would not disclose it to protect other congregations.

Brown’s 2006 op-ed calling for the BGCT to make the list public led to an outpouring of survivor stories. Brown says she created the Stop Baptist Predators website to track accused pastors because SBC leaders refused to act. She ultimately documented 170 names of credibly accused abusers and says she endured severe retaliation, threats, and smear campaigns. Brown claims SBC leaders labeled her and other SNAP advocates as “evildoers” and compared them to criminals.

Brown says that for 17 years she pleaded for a public database of abusers. She also pushed for a truth and reconciliation commission. Working alone with her legal background, she used a basic website and social media to expose patterns of institutional failure in a denomination with a multi-billion dollar infrastructure. Brown suggests this imbalance illustrates the depth of resistance to accountability.

Brown also supported other survivors, including Jules Woodson, whose story of abuse by youth pastor Andy Savage gained national attention in 2018. Brown says Woodson’s experience mirrored her own, from being groomed by a trusted pastor to being shamed by church members after reporting what happened. Brown argues that Woodson’s story and others like it demonstrate a longstanding pattern of churches protecting abusers instead of children.

Brown recalls standing before survivors in 2019 at an outdoor rally held only yards from a dumpster because SBC leaders refused to allow the event inside the convention hall. She says that despite the heat and noise, she felt profound hope in the unity of survivors who refused to be silent. Brown asked how many more children would be harmed before leaders finally acted. Behind her, another survivor held a sign that read, “I can call it evil because I know what goodness is.”

Brown says this movement, built from survivor testimony, investigative reporting, and years of pressure, is the only reason the broader public now understands the scale of sexual abuse within the Southern Baptist Convention. Brown maintains that minimizing the rape of older children is part of the same culture that enabled her pastor and so many others. She concludes that all child rape is catastrophic, that every survivor deserves dignity, and that no public figure should ever defend predators, directly or indirectly.